In 1086, a Great Survey was carried out on behalf of William the Conqueror for what became known as the Domesday Book. Clerks were sent out to every shire to record the ownership of every piece of land and assess its value to the king. Oswestry was not mentioned by name, but a new castle was recorded, and a church, within the manor of Meresberie (modern day Maesbury).

The early history of St Oswald’s is shadowy, and it is not known if there was a church on the present site prior to the Norman Conquest. It is known that in 1121 the church of St Oswald is listed in the possessions of Shrewsbury Abbey. In 1223 the Abbey appointed our first vicar, Philip Fitzleofth.

So, how old is the church?

The oldest part of the present building is the lower part of the tower. This, with the wall between the tower and the West Door, including the small lancet window, is thought to be from the 13th century.

Oswestry was a ‘frontier’ town, the scene of several violent attacks at that time, so it is not surprising that so little remains of the original building, and that what is left of the tower has been much repaired and added to. Rev. David Cranage, writing at the end of the nineteenth century, noted that the tower is buttressed on all walls, including the sides now inside the church, raising the possibility that it was “built as an addition to a Norman or Saxon building and it may have been quite separate from it.”

THE CIVIL WAR

Much was to disappear in the Civil War when great damage was done. Richard Gough of Myddle, writing in the early 1700s, described how “The Governor of this towne when it was a Garrison for the King pulled downe many houses that were without the Wall lest they shelter an enemy. The Church also beeing without the Wall was pulled downe, and the toppe of the Steeple unto that loft where the bell-frame stood. The belles were brought into the Towne.” The ‘squinches’ or masonry supports for the upper structure can still be seen inside the tower in the clock room.

The battle took place on the 22nd and 23rd of June 1644. The church was quickly taken by the Parliamentary forces and the New Gate breached. The Roundheads took the town, forcing the Royalists in the castle to surrender.

the New Gate breached. The Roundheads took the town, forcing the Royalists in the castle to surrender.

It is claimed that the church was used as a stable. The damage caused at this time took more than fifty years to repair. The tower buttresses were strengthened and a larger one added on the west side to stabilise the tower, and the lower section of the spiral staircase was filled in with stone.

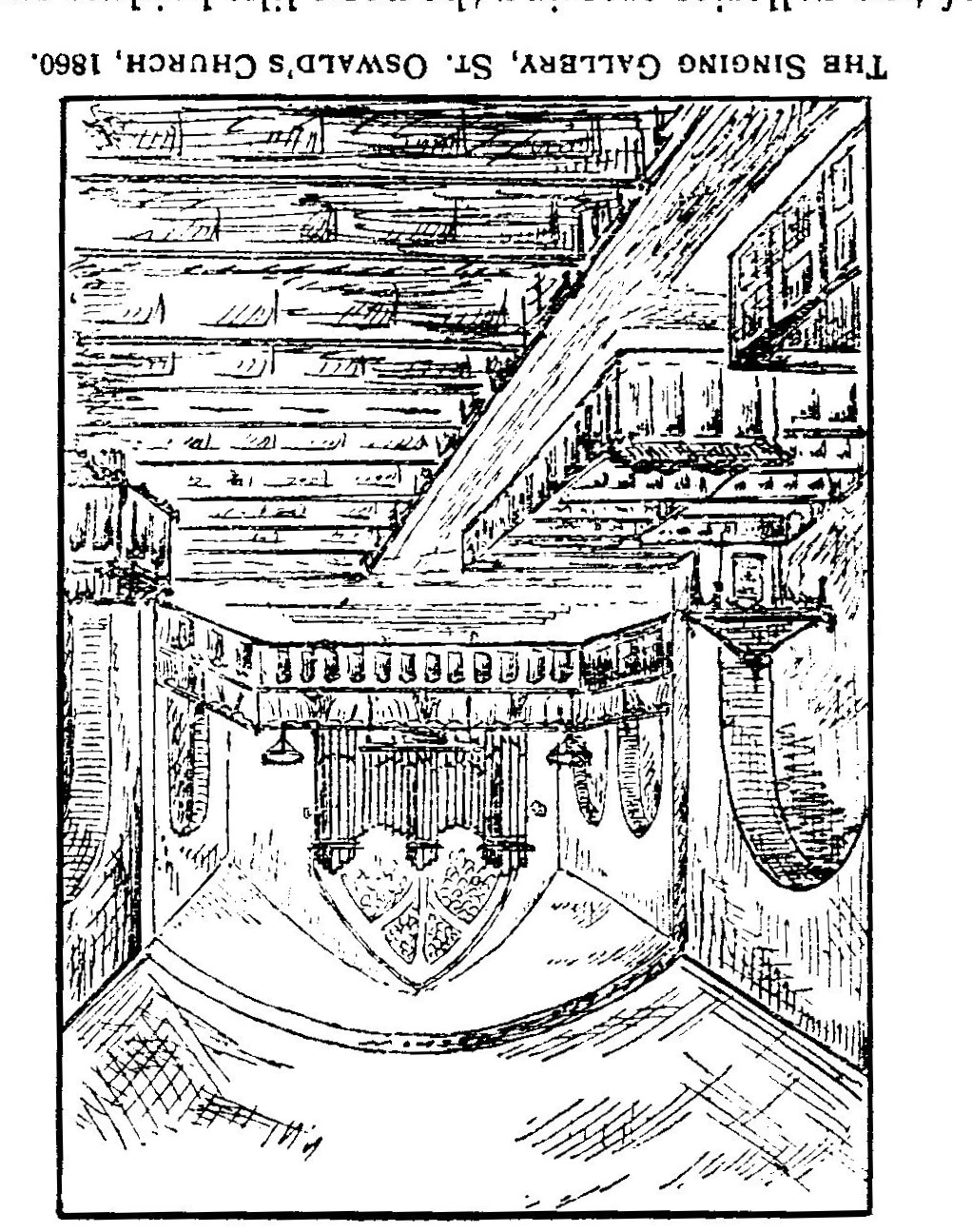

Between 1700 and 1870, the church was very crowded, with box pews owned by the well- to-do. ‘Free seats’ were attached to the ends of the box pews for the poor, although that left little space in the aisles.

Several galleries were added to provide more seating, including two across the chancel for the choir and the organ. But with a growing population, space was insufficient for the town’s needs, leading to the establishment of a second Anglican church, Holy Trinity in Roft Street, in 1837.

THE VICTORIAN RESTORATION

The church underwent a full restoration in 1872-4 by the architect G. E. Street. Box pews and galleries were swept away. The nave, the body of the church, had a new roof, floor, pillars and windows. Meanwhile, for two years the congregation worshipped in the National School in Welsh Walls and in Oswestry School Chapel. There was a whole week of music to celebrate the re-opening, and there were 1500 people present at the final celebratory service, sitting on chairs, as the church’s new pews had been lost in a fire at the premises in Shifnal where they were being made.

Prior to Street’s restoration of the church, much of the floor had been paved with the gravestones of those buried beneath, heavily worn by feet in places. The floor was to be lowered, and the plan was to bury these stones under the new floor, having recorded their position and inscription. There were objections to this, as many of the bodies had been buried within living memory.

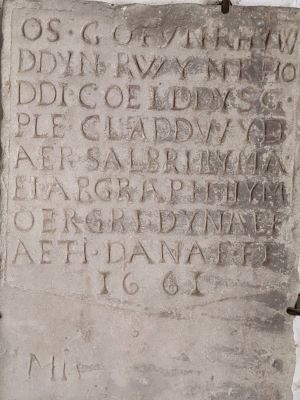

Approximately seventy gravestones remain under the nave floor, many others were eventually piled around the perimeter wall of the churchyard, and twenty-two were transported up to the first floor of the tower (presumably with great difficulty!) and fixed to the walls. Among them is a stone with an inscription in old Welsh in the form of an ‘Englyn’, a poem written to a strict format. The stone is dated 1661 and is thought to be one of the oldest of its type. The inscription reads:

OS·GOFYN RHYW

DDYN RWYN RHO

DDI COELDDDYSG

PLE CLADDWYD

AER SALBRI LLYMA

EI ARGRAPH LLYMA

OERGRI DYNA EF

AETH DANAF FI

TRANSLATION:-

"IF ANY MAN SHOULD ASK

I GIVE CERTAIN KNOWLEDGE

WHERE SALBRI'S HEIR WAS BURIED

HERE'S HIS IMPRESSION, A

COLD, SHARP CRY,

HE IS THE ONE PLACED UNDER ME.

The identity of Salbri or Salisbury, is a mystery. Dr. Guto Rhys says: “This is a VERY important monument. It is one of the very earliest englynion on a grave, and therefore a prestigious monument, testimony to the fact that Welsh was most important in the high culture of the town.” The stone appears to have been re-used, as there is an inscription below, in a different ‘hand’ to a “Mis Dorithy Ellis”.